THE FANTASY OF REPRESENTATION

Essay by Andrew Salgado

What counts is seeing, coupled with fantasy, with imagination…

– Josef Albers

It may seem paradoxical, perhaps, that an exhibition based on the wonderment of representational painting should lead with a quote by Josef Albers – one of the most regarded and unforgiving modernists of the 20th century. However Albers, as educator, theorist, stylist, and technician, has had some of the most profound effects on the world of contemporary painting, as any other leading artist. In some instances, his breakthroughs in colour-theory, and his insistence on the importance of the eye and the subsequent cognitive processes (as it relates to our understanding of art), can be read across discipline, media, or intent. These are not ideas beholden to abstraction, but ideas of abstraction that have bled into the other disciplines. They prove, above all, that fantasy lurks in even the most austere corners of representation. In some respects, as an artist myself, I often find myself returning to simpler ideas to find deeper complexities in my understanding (and execution) of art: ideas such as those laid out by Albers, to understand the challenges of a work, by, for instance, Francis Bacon, who is largely regarded as the greatest painter of the second half of the 20th century. The stark, uncharacteristic and often uncompromising combinations, favoured by Albers, can assist in our understanding of the unlikely combinations in some latter-career Bacons: where those unearthly pinks, lustrous ochres, blood-deep maroons, and army-greens truly come alive.

I’m inclined to discuss the paradox of the representational artist (I imagined Albers and Bacon in a boxing ring, though I’m sure nothing could be further from the truth), which introduces a disjuncture, to which the practice of the representational artist has been challenged, by those pure abstractionists. Today, it’s quite trendy to mutter the word ‘representational’ as some sort of pejorative term: that as representational artists, we are somehow less enlightened – clinging on to some banality of representation, as though aesthetically remiss or delayed in our artistic development, like we haven’t quite evolved into the higher realm of pure abstraction. Recently, during a studio visit I commented that for the first time in my own art practice, the ‘background’ held as much importance as the figure. My visitor asked, innocently enough: “then why do you still feel the need to paint the figure?” My response, simply enough: “Because I want to.”

When looking at the contemporary abstractionists, the representational artists are expected to get it, (we do get it – you would never believe some of the abstractionists whose work I frequently look to for inspiration) and frankly, my practice has become stronger as a result. But the contemporary abstractionists do not look to us: they are not expected to get our practice. Such is one of art’s bitter ironies. The truth is, in accepting abstraction into our vernacular, the representational painter has become ambidextrous. We speak two languages; we are visually acrobatic: like moles in fake moustaches, infiltrating enemy headquarters, sleeping with their women, drinking their gin, but reporting back to that world of representation – often with a wink and a nod. But with our embrasure of abstraction, we have welcomed fantasy. Who knows, perhaps it is our Achilles tendon that we retain a desire to locate, anchor, inform; that paroxysm where a brushmark becomes a reference.

Truthfully, the intention of this exhibition is to showcase the work of talented painters, both emerging and established, who, I believe, are exciting representatives of the contemporary state of representational painting. An artist like Dale Adcock, for instance, straddles the line between such severe, stark abstraction, and pure imaginative figuration, so that classifying him as either seems impossible. Sverre Bjertnes transcends the expectations of the figurative artist: both hyper-real and ‘not-at-all-real’, a stylistic schizophrenic. In discussion on the telephone with Scott Anderson’s Los Angeles representation, we both referred to him, very casually and confidently, as a representational painter, and personally, I love that duality, where his work – ostensibly completely abstract – is actually anchored in some dreamy, shape-shifting (sur)reality. I see a tree. I see eyes. I see a monster. It makes my mind work… Tick tock, tick tock, tick tock…

I’m reminded of a seminal and telling essay on Cézanne by the celebrated essayist Clement Greenberg[i] in which the critic credits the influential Modernist with separating the thing or (for you art-nerds out there)referent from its painted depiction to its essence, reduced to a colour, a feeling, a suggestion in planar space. Chuck Close writes something similar when he criticizes (or at least critiques) Andrew Wyeth’s remarkable Christina’s World[ii], for erroneously painting each blade of grass (I imagine him saying this with some long-held disdain for the banalities of grass), as opposed to painting the idea of the grass. The naked eye cannot distinguish between blades, and as such, Close considers the divorce from verisimilitude as tantamount. An interesting argument, but Close is simultaneously a hyperrealist and a totally abstract painter (just look at his catalogue of works). A similar feat is made by Alexander Tinei, where superficial brushstrokes suggest a tattoo or a tribal mark, but perhaps appear from merely the artist’s whim to decorate, and though that has become such an ugly term in contemporary artspeak, I question much purely abstract art, which seems to have gone so far down the rabbit-hole that it has doubled back upon itself: entirely abstract art is often purely decorative, at times blank, (is the word pointless too accusatory?), often distancing or just too plainly hard to decipher. Is that a bad thing? Not necessarily. In fact I love abstraction. I am often drawn more to purely abstract painting than I am to representational painting, but nobody likes to feel like the wool is being pulled over their eyes. In the best sense, it is evident that representational art is being pulled from its roots (just like grass!) and pushed into abstraction. I look at Justin Ogilvie’s Peasant paintings and think: yes! Here a mark might be an eye, but on another level, it is only a mark, the essence of a thing, always abstract, always representational, always somewhere in between. And what a beautiful thought that is! I’m reminded of the Kate Bush song where she sings about The Painter when she croons, “lines like these must be an architect’s dream”.[iii]

Above all, this exhibition is something of a celebration of painters: a series of representational painters’ painters, who illustrate the infinitesimal possibilities of imagination, as introduced by representation; its bounds, and our desire (as artists and viewers alike), to transcend, to challenge and to subvert. And it is a vanity project, I guess, inasmuch as it allows me the opportunity, as an artist, to wear the mask of a curator, if only to momentarily present a group of artists from different eras, nations, styles, and movements, for no other reason than to celebrate their influence on (not only my own tiny practice, but) the state of representational painting today as a whole. Towards a new language of representation, where these lines are blurred, and what we are left with is not unlike a painting by Albers: a series of lines, colours, and delineations, only within the picture plane itself, to be deconstructed and reassembled as we please, limited only by the imagination of the viewer.

[1] Clement Greenberg. “Cézanne: The Gateway to Painting.” The American Mercury. 1952.

[1] Chuck Close. “The Great Illusionist.” Financial Times. 2006.

[1] Kate Bush. “An Architect’s Dream.” Aerial. 2005.

Essay by esteemed art critic Edward Lucie-Smith

‘THE WAY I SEE IT IS NOT THE WAY YOU SEE IT’

In the last few years, a lot of artists – and with them the curators who are their eager supporters – have been advancing a new theory of figurative art. This, like so many things in the contemporary art scene, bases itself on a paradox. The paradox is that appropriated images are in fact the most original things a would-be avant-gardist can present to his or her audience.

This proposition has both deep roots and shallow ones. The deep roots are to be found in the long-established Western studio tradition, dating at least as far back as the Bolognese academy of the closing years of the 16thcentury, that young artists, rather than starting ab initio, must learn to build of the achievements of their predecessors. A rather similar attitude prevailed in China, after the fall of the Ming Dynasty, when court painters were more anxious to produce landscapes ‘in the manner of’ respected Song and Yuan masters than to portray anything they actually saw.

The shallow roots are in Pop Art, which encouraged artists to identify with contemporary mass culture by appropriating images from films and publicity photos of film stars, from news photographs, from advertising, and from a wide variety of other non-art sources. This practice has now reached a second stage. A recent show at the Saatchi Gallery, for example, offered a near identical version of an Andy Warhol Elvis, signed by a painter from Belorussia, and, venturing into classier territory, an upside-down copy of a well-known painting by Fragonard – the original is now in the Wallace Collection. Both of these were presented as radically creative efforts to push forward the frontiers of avant-gardism. After careful scrutiny, I couldn’t think why either artwork should interest me. Been there, done that. The only pleasure either them could offer was a smug little voice in one’s head, saying: “Clever me, I’m one of the gang – I know what the original is.”

Given the fact that the original Modern Movement, which got its start at the beginning of the 20th century, placed such emphasis on original ways of seeing the surrounding, contingent world; and given, too, that the Modernist impulse, though now quite distant from us, still governs so many of our reactions to the idea of art, regarded as a process of making images, it is not surprising that some artists have again begun to rebel, and to look for ways of presenting images that a wholly and unmistakably personal. The results are what the visitor sees in this exhibition.

The artists selected range from a few who might be described as Old Masters – at least within the selected terms of the event – to names that will be new to most people. There is, deliberately, no consistency of style. Andrew Salgado, the distinguished younger artist who has put the show together, speaks of “our desire (as artists and viewers alike), to transcend, to challenge and to subvert.” I think the event does exactly that. A large part of its subversive effect, to me at least, is that it makes it very clear that much supposedly progressive art, as currently blessed by so many of our official institutions, is begging for a massive kick up the backside. I’m tired of looking at ho-hum art. This seems to offer a way out.

DALE ADCOCK

DALE ADCOCK (b. 1980, Leicestershire, UK) holds an MA in Art & Design from the Chelsea College of Art and a BA in Fine Art (Painting) from the Wimbledon School of Art. Selected shows and projects include The Future Can Wait, Victoria House, London (2014), ‘100 Painters of Tomorrow’ Book Launch, Christies, Kings Street (2014), Perfectionism, Griffin Gallery, London (2014), The Fine Line, Identity Gallery, Hong Kong, China (2013), Alter, Vegas Gallery, London, UK (2012), The Perfect Nude, Charlie Smith Gallery, London (2012), Polemically Small, Orleans House, London (2012), House of the Nobleman, Boswall House, London and the Future Can Wait, Victoria House, London (2011). Adcock is also included in the recent Thames & Hudson publication titled ‘100 Painters of Tomorrow’ by Kurt Beers.

HURVIN ANDERSON

Anderson’s paintings flirt between abstraction and figuration, their tranquil scenes merging unstable ideas of memory, conjoined histories, and cross-culturalism. Peter’s Sitter’s 3 imagines a home barbershop, a cottage industry taken up by many newly arrived Caribbean immigrants in the 1950s. Rendered in a reduced palette of blue, white, and red, the scene conveys the experience of freshly acquired British identity, its aspirations and hard realities. The brilliant tones and translucent veneers of the floor and ceiling hark to the open expanse of tropical seaside, while the opaque geometric walls and modest furnishings create a rigidly grounded environment, conveying a sense of disorientation and displacement.

Anderson was born in Birmingham in 1965 to parents of Jamaican origin. He was educated at Wimbledon College of Art, London and The Royal College of Art.

SCOTT ANDERSON

Scott Anderson’s work has been described by writer David Pagel as “dystopian abstraction.” Using bright colored abstraction juxtaposed with figurative elements, the work takes on a surreal quality resplendent with apocalyptic connotations. His work is concerned with moments of cultural upheaval steeped in capitalism and bygone political revolutions. For his show at CES, Anderson’s work remarks upon the loan figures as satirical icons of popular culture, including the controversial Slavoj Žižek.

Anderson received his BFA from Kansas State University and his MFA from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His work is also in the permanent collection of Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art. Anderson has participated in exhibitions at MCA Chicago, the Parrish Art Museum, The Warhol Museum and the Cranbrook Art Museum. He has exhibited in Solo and group shows at Kavi Gupta in Chicago and most recently with CES Gallery this spring. His work has been featured in numerous publications including: The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, Beautiful Decay, Daily Serving, and Bon Magazine. Anderson has been the recipient of the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant, The William and Dorothy Yeck Award and was most recently awarded inclusion at the prestigious Skowhegan Artists Residency.

FRANCIS BACON

Born to an English family in Dublin on 28 October 1909, Francis Bacon was the second of five children of Christina Firth, a steel heiress, and Edward Bacon, a race-horse trainer and former army officer. His childhood, spent at Cannycourt, County Kildare, was blighted by asthma from which he suffered throughout his life. With the outbreak of war in 1914, his father took the family to London and joined the Ministry of War; they divided the post-war years between London and Ireland. Bacon repeatedly ran away from his school in Cheltenham (1924-6). After his authoritarian father, repelled by his burgeoning homosexuality, threw him out of the family home for wearing his mother’s clothes, Bacon arrived in London in 1926 with little schooling but with a weekly allowance of £3 from his mother.

In 1927 Bacon travelled to Berlin (frequenting the city’s homosexual night-clubs) and Paris. He was impressed by Picasso’s 1927 exhibition (Galerie Paul Rosenberg) and began to draw and paint while attending the free Academies. Returning to London in the following year, he established himself (and his childhood nanny Jessie Lightfoot) at Queensbury Mews West, South Kensington. He worked as a furniture and interior designer in the modernist style of Eileen Gray and exhibited his designs there in 1929. These were featured in the Studio 1 before he shared a second studio show with the painters Jean Shepeard and Roy de Maistre (Nov. 1930). An early patron was the businessman, Eric Hall, who would become Bacon’s lover and supporter (c.1934- c.1950). As well as designing, Bacon continued to paint with de Maistre as an important influence and practical guide on matters of technique. The results showed the impact of Jean Lurçat and Picasso, and a Crucifixion shown at the Mayor Gallery in 1933 was juxtaposed with a Picasso in Herbert Read’s Art Now and bought by the collector Sir Michael Sadler. In the following year, the painter organised his first solo exhibition in the basement of a friend’s house (Sunderland House, Curzon Street) renamed ‘Transition Gallery’ for the purpose, but it was not well received and he responded by destroying the paintings. His works were rejected by Read for the International Surrealist Exhibition (1936), but Bacon and de Maistre helped Hall to organise Young British Painters (Agnew and Sons, Jan. 1937), which included Graham Sutherland, Victor Pasmore and others.

With the coming of war in 1939, Bacon was exempt from military service and released by the ARP on account of his asthma. He spent 1941 painting in Hampshire, before returning to London where he met Lucian Freud and was close to Sutherland. From these years emerged the works which he later considered as the beginning of his career, pre-eminently the partial bodies of Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 1944 (Tate Gallery N06171) which was first shown at the Lefevre Gallery (April 1945) to unease and acclaim alike. Bacon became central to an artistic milieu in post-war Soho, which included Lucian Freud, Michael Andrews, the photographer John Deakin, Henrietta Moraes, Isabel Rawsthorne and others. On Sutherland’s recommendation Erica Brausen secured the painter’s contract with the Hanover Gallery and sold the painting in 1946 to the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1948. Bacon gambled away the results at Monte Carlo and, as homosexuality remained illegal, his lifestyle in London and France was tinged with the illicit.

The early 1950s saw a period of success and rootlessness following the death of Jessie Lightfoot. Bacon’s first post-war solo exhibition included the first of many works inspired by Velazquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1650 (Galleria Doria Pamphili, Rome) and showed his use of characteristic enclosing frameworks (Hanover Gallery, December 1951 – February 1952); it was followed by his New York debut (Durlacher Gallery, October 1953). The paintings of Popes, which established his reputation, alternated with those of contemporary figures in suits who were similarly entrapped; however, following a trip to Egypt and South Africa (1950) a lighter tonality emerged in paintings of sphinxes and of animals. During this period, Peter Lacey became Bacon’s lover and inspired homoerotic images of wrestlers derived from Eadweard Muybridge’s photographs in Animal Locomotion (Philadelphia 1887), Animals in Motion (London 1899) and The Human Figure in Motion (London 1901); the photographs became a habitual source, just as the theme of sexual encounter persisted. In Italy in 1954, Bacon avoided seeing Velazquez’s Pope Innocent X in Rome and his own paintings at the Venice Biennale, where he shared the British pavilion with Ben Nicholson and Freud. Two years later, he visited Lacey in Tangiers, and met the American writers William Burroughs and Paul Bowles, and the painter Ahmed Yacoubi; Bacon subsequently returned regularly until Lacey’s death in 1962.

The exhibition of paintings after Van Gogh (Hanover Gallery, 1957) marked the sudden departure from the preceding monochromatic works towards heightened colour. Despite their success, in the following year the painter transferred dealer to Marlborough Fine Art; they paid off his growing gambling debts, mounted larger exhibitions and ensured that he destroyed fewer canvases. In 1961, Bacon settled in Reece Mews, South Kensington, where he remained for the rest of his life, and in the following year the Tate Gallery organised a major touring retrospective which saw the resumption of his use of the triptych which would become his characteristic format. At that time he recorded the first of the interviews with the critic David Sylvester which would constitute the canonical text on his own work.

In 1963-4, Bacon’s international reputation was confirmed with his retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (1963) and by the publication of Ronald Alley’s catalogue raisonée. He refused the Carnegie Institute Award (1967) and donated the Rubens Prize towards the restorations following the flood of Florence. On the eve of Bacon’s large retrospective at the Grand Palais in Paris (1971), his long-time lover George Dyer committed suicide and this event left haunting echoes in ensuing paintings. However in 1974, John Edwards became the painter’s companion and model.

In the 1970s Bacon travelled regularly to New York and Paris, where he bought a pied-à-terre, and publications helped to establish the popular image of his work as a reflection of the anxiety of the modern condition. International exhibitions became more wide-ranging: Marseilles (1976), Mexico and Caracas (1977), Madrid and Barcelona (1978), Tokyo (1983). They reinforced the perception of Bacon as the greatest British painter since J.M.W. Turner. His works from this period were dominated by the triptych, but the figures grew calmer and were set against flat expanses of colour. In isolated images without a human presence, an animal power was retained in segments of dune and waste land. The exhibitions culminated in a second Tate retrospective (1985, travelling to Stuttgart and Berlin), and shows in Moscow (1988) – a sign of post-Communist liberalism – and Washington (1989). On a visit to Madrid in 1992, Bacon was hospitalised with pneumonia exacerbated by asthma and died on 28 April.

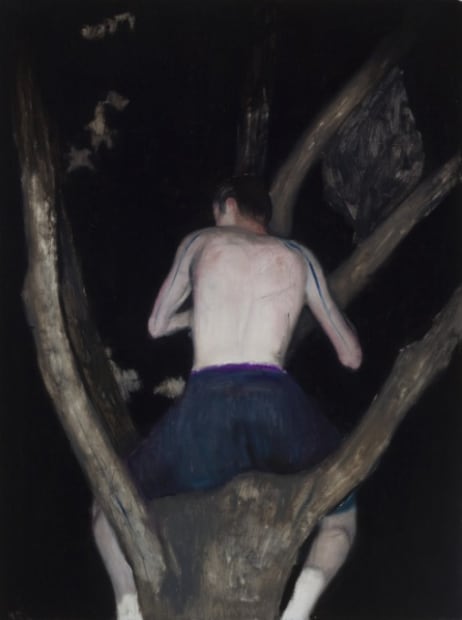

SVERRE BJERTNAES

Sverre Bjertnæs (1976, Trondheim) was educated at the Norwegian National Academy of Fine Arts in Oslo, for then to further develop his studies at AKI Academy of Fine Art in Enschede in Holland. During the most recent years, he has been rising as a star in Norway’s contemporary art scene, with a strong artistic identity.

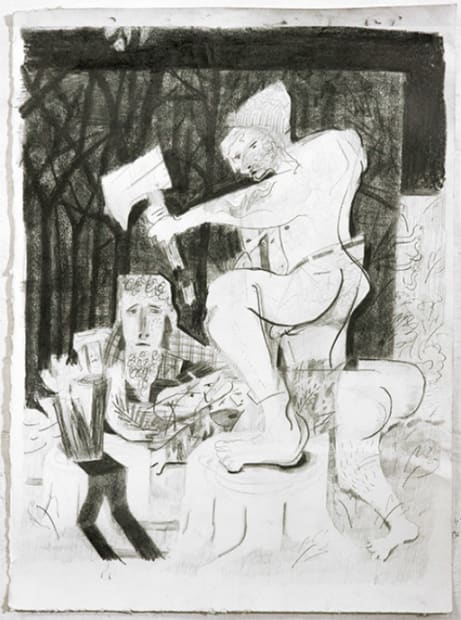

He made his mark as a young figurative painter and drawer after attending the Norwegian “Nerderum School” as a teenager. Bjertnæs’ paintings frequently display portraits, where a playful tone meets the images complex relationships. These perspectives have in the latest years formed a unique language. Each work is a new discovery equipped with its own codes and instruments, an exciting artistic style that both stays true to classical figuration, as well as experimenting with conceptualism. His works, Bjertnæs states, are focused on the community between the works and the viewer as an aesthetic experience. This transition between styles have had a groundbreaking effect on Bjertnæs’ oeuvre, where the focus is the exploration in itself, both of the arts own possibilities and of himself.

ALISON BLICKLE

My paintings let me live out fantasies through characters I create. These stories often involve my desire to feel a connection to something bigger than myself– to nature, to my ancestors, or to a sense of spirituality. I’ve created an alter ego who appears as a recurring protagonist in my paintings. This imaginary version of me is who I wish I could be– a strong, fearless hero engaged in exploration and adventures.

I like to daydream about living in the woods, being completely at home in the wilderness, and having an intuitive understanding of the living things around me. In reality, when I find myself in a forest or in a desert canyon, I don’t have the profound sense of belonging that I expect. Instead I feel like a spectator in a beautiful, mysterious world that is not mine. It’s too far removed from the world I belong to. A deep connection to nature is at odds with our current culture, but I want to be a part of both of them. An aspect of my work explores the question– how can we stay in touch with the wild parts of ourselves while living within the order of a “civilized” way of life?

My family is full of eccentrics. A chat on the phone may involve topics like shamanism, animal guides, wicca, tree-sitting, talking to plants, or hypnotherapy. People often turn to these kinds of practices for a sense of belonging and meaning that is lacking in our culture. While my logical side can’t help but judge these practices as wishful thinking, part of me believes they are real. They offer the potential for the world to be a fantastical place. My work touches on the conflict between my attraction to mystical tradition, and my skepticism of it. – Alison Blickle (1976, Los Angeles)

DANIEL CREWS-CHUBB

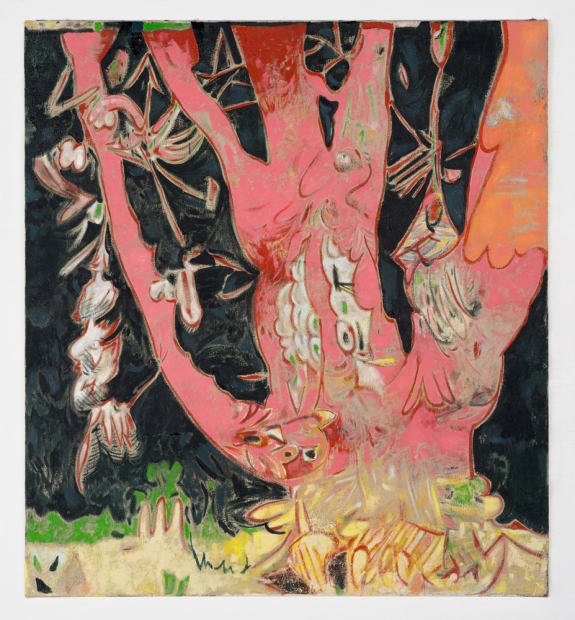

Crews-Chubb’s practice consists of paintings on canvas and paper in which the figures are informed by primitive art and culture as well as pornographic imagery found online. The works demonstrate a seemingly unfinished aesthetic created using a range of methods including collage and spray paint to create language where areas of impasto connect with areas of raw canvas. The works therefore offer the viewer a moment captured in the process of production as opposed to a pristine ‘complete painting’. The paintings share a perverse playfulness often linked to abstract expressionism which stems from the artist’s fondness of painters such as William De Kooning and George Baselitz as well as the European Avant-Guard movement COBRA – where the works were based on spontaneity and experiment and drew inspiration from children’s drawings. The grotesquery associated with Crews- Chubb’s figures derives from notions of existential doubt and the human inability to find an inherent purpose. The works often make references to ancient gods, ritualistic acts and other existential concepts.

DANIEL CREWS-CHUBB (b. 1984, Northampton, United Kingdom) gained his Fine Art BA (HONS) degree from Chelsea College of the Arts in 2009, before completing a year-long alternative postgraduate painting programme in 2013 at Turps Banana founded by Marcus Harvey. He has exhibited regularly in group shows including the Crash Open 2013 selected by Phillip Allen and Neal Tait, and Creakside Open 2013 selected by Paul Noble as well as winning BEERS London prize for emerging art in 2014. Daniel currently lives and works in London, UK.

BLAKE DANIELS

Blake Daniels looks at the way a body is constituted by its surroundings, constructed spaces that are never as innocent as they portray. His paintings depict bodies and spaces that are constantly being altered, dislocated, and fragmented through the internalization of the socially built spaces they experience. Figure and ground relations must be reconfigured, and imagined, to account for the inherent hybridism that has arisen between representation and abstraction. This shift within Daniels paintings speaks to larger postcolonial conditions, contesting notions of pure race, gender, language and nationality. A combative shift of the body’s relation to space used to create identities non-contingent on linear narratives. A new ‘real’ no longer reliant on bearing the weight of fixed social algorithms. Left in the wake of late 20th century deconstructionism, Daniels work interrogates these fractures that oft constitute the ‘bastard’; inventing a wild and playful, yet astutely dark conception of his observed world.

BLAKE DANIELS (b. 1990, United States), a recipient of the Edward L. Ryerson Fellowship from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, has worked and exhibited across the United States, South Africa, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Canada and the United Kingdom. His large-scale paintings map abstraction directly onto figure and space, demanding a reinterpretation of how painting functions within the conditions of the twenty first century. Exhibitions include New Work, Sullivan Gallery, Chicago, Illinois (January 2013); the Free City International Arts Festival, Chevy-in-the-Hole Gallery, Flint, Michigan (May 2013); Mapping the Abstract, BEERS London, United Kingdom (August 2013) That Ship Has Sailed, Edna Manley College of Visual and Performing Arts, Kingston, Jamaica (October 2013); amongst Daniels participation in the Rex Nettleford Arts Conference with the Edna Manley College of Visual and Performing Arts in Kingston, Jamaica and the Meeting Place: Caribbean InTransit Symposium with the University of the West Indies in St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago.

ECKART HAHN

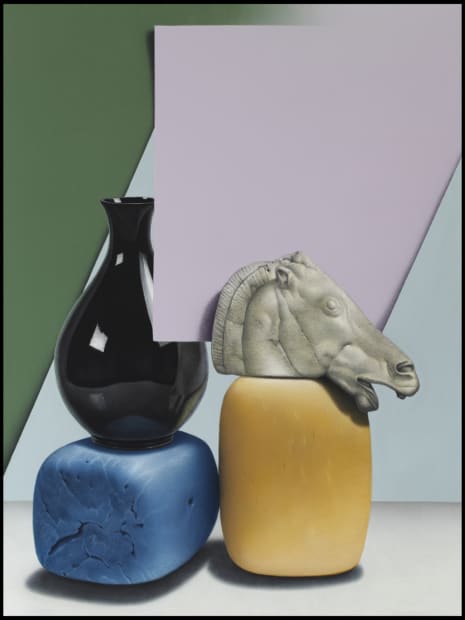

“Eckart Hahn is an uncanny perfect painter, who entirely in accordance with traditions has a complete mastery of his handwork. The central-perspective illusionism in his pictures can hardly prevent us from recognizing his art as being a product of visual inventions from the deepest interior of his spirit. The collage-like combination of spaces and objects and the processes which at first glance appear to evade all rational understanding, which appear in these pictures, belong to expression of this uncanniness.”

AARON HOLZ

Aaron Holz’s work explores the materiality of paint and the psychological space in and around the figures and objects he depicts. Often referencing painters as divergent as Goya and Darger, Holz combines this dialogue with past practitioners with found contemporary images of wrestlers, sunbathers, floral arrangements and landscape. The diverse nature and utilization of mediums pushes the paintings into a purposely-conflated world of illusion and abstraction. The result is work brimming with desire and longing for a world rendered illusory through unusual juxtapositions of subject matter, heightened and saturated colors, and vertiginous special arrangements.

AARON HOLZ (b.1972, USA). Aaron Holz’ solo exhibitions include A Heart’s Hot Shell, Rare Gallery, New York, New York (2011); Of Heads & Hands, Focus Gallery, Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln, USA (2010); Portraits, Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts, Nebraska City, USA (2009); Takedown, Rourke Art Museum, Moorhead, Minnesota, USA (2009). Group exhibitions and Projects include [When We Dead Awaken]; BEERS London, (Feb 2012); [After School Special], University Art Museum, Albany, New York (2011); What Would Dante Do? Rourke Art Museum, Moorhead, Minnesota, USA (2011); Single Fare, 224 Grand, Brooklyn, New York, (2010); and Face Forward, LeRoy Neiman Gallery, New York, New York, (2009), He is recipient of the Harold & Esther Edgerton Assistant Professor of Painting Award (2009); and the Nebraska Artists Council Distinguished Artist Award (2007). His work has been published in the New York Times, Lincoln Journal Star, and NY Arts Magazine. He holds a Master’s degree from University at Albany, New York, and lives and works in the United States.

GARY HUME

English painter, draughtsman and printmaker. Hume emerged as one of the leading figures of the group of young artists working in London in the 1990s. His glossy, popular imagery captured and defined a zeitgeist, at a time when the art scene was becoming increasingly professionalised and implicated with the popular media. After graduating from Goldsmiths College, London, in 1988, he achieved early success with paintings based on hospital doors, rendered with gloss on panel and displayed in groups of four. These works had an international appeal. Despite their success, Hume abandoned the formal manoeuvering of the door series in the early 1990s, in favour of a simple, flatly coloured representational style drawing on a broad pool of popular and prosaic subject-matter. Hume’s own admission of the superficial role of such subject-matter points to the role of figurative imagery as a stimulant to his primary preoccupations of structure, surface and colour. The concentration on both literal and metaphoric surface was augmented by the change from panel to aluminium support effected in the mid 1990s, at which point he began to focus, in his own words, on ‘flora, fauna and portraiture’. While paintings such as the disarmingly touching portrait of Francis Bacon, Francis (1997; priv. col., see 1999–2000 exh. cat.), show an indebtedness to pop-art overstatement, othersdemonstrate an affinity with the more introverted painting of Patrick Caulfield. Hume was shortlisted for the Turner prize in 1996 and represented Britain at the 48th Venice Biennale in 1999.

ADAM LEE

Adam Lee works from his studio in the hills of the Macedon Ranges, Victoria, and he works mostly with traditional painting and drawing materials. His work references a wide range of sources including historical and colonial photography, biblical narratives, natural history and contemporary music, film and literature to investigate aspects of the human condition in relation to ideas of temporal and supernatural worlds.

ADAM LEE (b.1979, Melbourne, Australia) received his Bachelor of Arts, Fine Art (Painting) from the Royal Melbourne Institute of technology. Lee continued his studies by completing his Masters by ‘Research In Fine Art’ from the Royal Melbourne Institute of technology and furthered his education by undertaking a PhD in Research Project at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. Lee has had solo presentations of his work, including Eden. Exile. Babel (2015) at Station, Melbourne, Into the Heart of the Sea and the Sea and to the Roots of the Mountains (2013) and The World Travailing (2012) at Kalimanrawlins, Melbourne and also, And They Build for Themselves Kingdoms (2011), Tristian Koenig, Melbourne. Lee has been shortlisted for numerous awards including the Geelong Contemporary Art Prize, Geelong Gallery, Geelong, Victoria, (2014). National Works on Paper Prize, Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery, Mornington, Victoria, (2014). The Arthur Guy Memorial Painting Prize, Bendigo Art Gallery, Bendigo, Victoria (2013). The Churchie National Emerging Artist Award, Griffith University, Brisbane (2012/11). Redlands Westpac Art Prize (nominated by Jon Cattapan), Mosman Art Gallery, Sydney (2010).

JENNY MORGAN

Centered on themes of life, death and rebirth, Jenny Morgan’s works question how we relate to our past and challenge us to live in the present. Fusing figurative realism with graphic forms, her impeccably detailed images demonstrate an exceptional technique, while purposefully abstracting the human body—at times literally reducing it to its fundamental, skeletal structure. She renders these darkly charged and psychological works in intense hues, revealing a life-affirming immediacy and spontaneity. Deeply personal, yet thoroughly universal, Morgan’s works achieve a striking intensity, breaking through the ideals of traditional portraiture and the preciousness of realism.

Her work has been the subject of solo exhibitions in New York, Colorado, Utah and Indiana; in numerous group exhibitions including the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C. and the 92Y Tribeca, New York; and at galleries in Florida, England and Sweden. Her work is represented in the collections of the Museum of Contemporary Art Jacksonville, Purdue University Art Gallery, University of Maryland’s Stamp Student Union Art Collection, as well as major private collections throughout the United States and abroad.

Morgan’s work has received critical attention in numerous publications including Juxtapoz, Whitewall, Hi-Fructose, The Village Voice, and The Denver Post. Her 2013 solo exhibition How To Find A Ghost at Driscoll Babcock Galleries was named one of the top 100 fall shows worldwide by Modern Painters. Her work has been the subject of three artist monographs, including Jenny Morgan: How To Find A Ghost (2013) authored by Benjamin Genocchio. Additionally, Morgan has realized several portraiture commissions for publications including The New York Times Magazine and New York Magazine.

Born in Salt Lake City, Utah, Jenny Morgan currently lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. She holds a BA from the Rocky Mountain College School of Design in Lakewood, Colorado and an MFA from the School of Visual Arts in New York, NY. Jenny Morgan has been exclusively represented by Driscoll Babcock Galleries since 2012.

JUSTIN OGILVIE

Justin Ogilvie is a figurative painter who received a MFA from the University of Alberta in 2013 and a BFA from Emily Carr University of Art and Design in 2000. Ogilvie’s professional career consists of both exhibiting and teaching. Between 2003- 08 he had four solo exhibitions with the Diane Farris Gallery in Vancouver, BC, another with the Douglas Udell Gallery in Edmonton, AB in 2010, as well as numerous group, municipal and artist run shows throughout. Since 2000, Ogilvie has been a committed art educator working with Emily Carr Continuing Education, the University of Alberta, Vancouver Film School and Vancouver School Board as Artist-in-Residence. Ogilvie is currently teaching at Emily Carr University of Art and Design. He has also operated an independent atelier providing a myriad of art courses ranging from traditional technique based courses, to the abstract, conceptual, as well as ongoing mentoring programs. The recipient of numerous provincial and private awards, and part of both national and international art collections, Ogilvie is committed to maintain his path as an artist and art educator. Ogilvie currently works out of his studio in Vancouver.

LOU ROS

Lou Ros, born in 1984, began painting at the age of 17. He started doing graffiti for fun with friends on the walls of buildings. But this game soon became a real addiction to him. Subsequently, the fast and spontaneous simple tag that he performed gave way to more sophisticated and substantial works like murals. Learning to paint on the job without going through art schools, Lou soon feels the limits of this street art, admitting himself that “there is an ethics of aesthetic beauty and repetition that eventually bores me. Painting beautiful is boring, while making a painting that has strength is quite another thing. So I started painting at home. ” Back home, he enriches his reasoning and his practice of painting by privileging an attitude of truth and a more fundamental quest to his painting, “The living and vibrant line instead of nice clean straight line.”

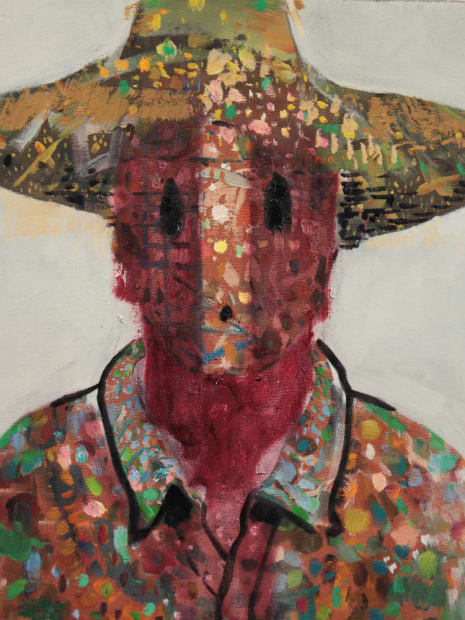

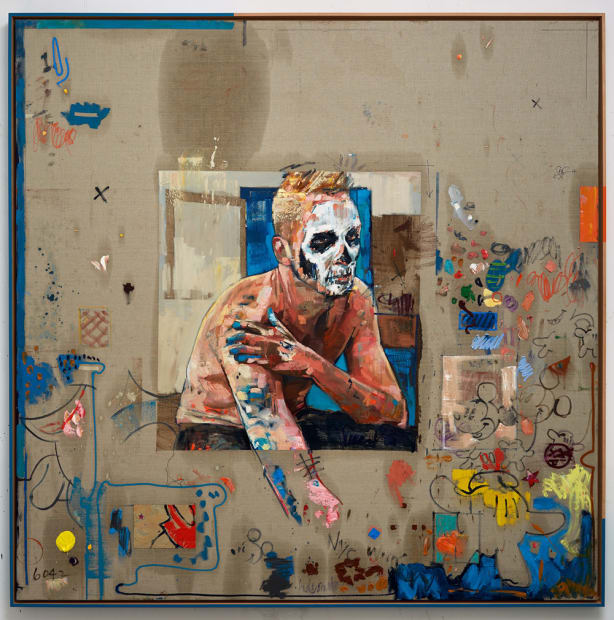

ANDREW SALGADO

The large scale, gestural paintings of Andrew Salgado works explore concepts relating to the destruction and reconstruction of identity – a process that he views as re-considering the conventions of figurative painting through a pursuit toward abstraction. To create paintings that engage beyond what is immediately visible, he often consciously questions the nature of identity (and painting) itself as something deconstructed, created, and tangible. A significant perspective of his work is concerned with the ‘monstrosity’ of the masculine form, incorporating Classical archetypes like the Laocoön or Dionysian, to subtle references to Guston, Bacon or even artists who exhibit a wild deviation from rules like Daniel Richter or Bjarne Melgaard. ”I am interested in how my paintings operate independently from their literal figurative foundation, and how they might deconstruct through colour choices, reduction of forms, and triumph of materiality.”

ANDREW SALGADO (b. 1982, Regina, Canada) has created a buzz for himself with bold, generally large scale figurative paintings that have situated him as one to watch in both the UK and North America; even being listed by Saatchi as “one of 12 to invest in today” (Sept 2013) and lauded by esteemed critic Edward Lucie Smith as a “dazzlingly skillful advocate” for painting. Salgado has exhibited in the United Kingdom, Germany, Scandinavia, Australia, Venezuela, Thailand, Korea, South Africa, Canada, and the USA. 2014 solo exhibitions include Enjoy the Silence, Christopher Møller Art, Cape Town (January), Variations on a Theme, One Art Space, New York City, NY (May) and Storytelling, BEERS London (October). In the fall of 2013 he exhibited in his first museum-based exhibition titled The Acquaintance, at the Art Gallery of Regina, Canada. Salgado’s paintings have hung alongside works by Tracy Emin and Gary Hume in London’s Courtauld Institute of the Arts included in the Merida Biennale of Contemporary Art (2010), the NordArt Carlshutte Biennale (2012); and has been featured Maclean’s (Canada), The Globe and Mail (Canada), The Independent, The Evening Standard, Saatchi Online, Shortlist, Yatzer, The Ottawa Citizen, The Metro (UK) and more. He frequently donates to charitable associations worldwide, including the Terence Higgins Trust, MacMillan Cancer Support, and garnered the highest-bid ever auctioned at Canada’s esteemed Friends For Life 18th Annual Charity Auction (2011). In 2011 he was featured in the Channel 4 (UK) documentary What Makes a Masterpiece, alongside artists Anish Kapoor, Howard Hodgkins, and Bridget Riley (2011). In 2013 he was commissioned to create a brand new series of large-scale works to adorn the windows of the luxurious UK-retailer, Harvey Nichols. He has lived and worked in London, UK since 2008.

DOMINIC SHEPHERD

Born in England in 1966 Dominic Shepherd studied Fine Art at Chelsea School of Art at both BA and MA level. He was a research fellowship at the AUB in 2008 and in 2004 Dominic was a prize winner at John Moores 23. He has exhibited internationally, with an extensive record of group and solo shows in London, Berlin, Los Angeles, Helsinki, Munich and Miami and is represented by Charlie Smith London. He is included in, and has written for, various publications. Presently he is co co-ordinator of the Black Mirror Network that explores the influence and role of Enchantment , the occult and magic in modernist and contemporary art. The first edition of a series of peer reviewed volumes, Black Mirror 0: Territory is being launched in October 2014.

ALEXANDER TINEI

Alexander Tinei (born 1967 in Căuşeni, Moldova) is a painter based in Budapest, Hungary. He has had solo exhibitions in New York City, Vienna, and Budapest and has been included in group exhibitions in London, Berlin, Frankfurt,